Invercargill’s David Brown never intended to build some of the best GT40s in the world, but his Kiwi know-how and can-do saw it happen almost by accident

Words: Andrew Johnston Photos: Andrew Johnston / Supplied

Buried deep in the South Island sits a business you may not have heard of but which is making waves around the globe. Classic Car Developments (CCD), the brainchild of born-and-bred Southlander David Brown, specializes in building meticulously accurate Jaguar C-Types and D-Types, and Ford GT40s. David didn’t set out to build what are now recognized as arguably the best Ford GT40 replicas in the world. Rather, building the cars just kind of evolved from the skill sets he had learnt and the people he was connecting with.

David’s engineering career started with Automotive Machining from 1966 to ’71. He then spent an enjoyable two years of performance-tuning race cars with Brian Taylor. Next up was six years of precision aircraft engineering and fabrication. During this time, David also had the opportunity to complete his private pilot’s licence and engineering licence exams for aircraft engineering. In 1980, he ventured into self-employment, starting his own engineering company called Mica Engineering, providing light engineering and working on race cars. After 10 years, however, he realized he wanted to specialize in building classic cars, starting with a full build of a beautiful Lotus 11. This was the beginning of CCD, starting with two C-Type Jaguar builds for overseas clients, a New Zealand–owned GT40, and a Ferrari Dino 206SP for Dennis Chapman in Christchurch.

The GT40 story began on a trip to Christchurch to deliver one of the C-Type Jaguars to be shipped to Sydney. The shipping agent invited Dave to dinner for a chat. After dinner, he said, “Come outside, I have something to show you.” He then led him out to the backyard where, behind a big heap of dirt, was a car of some sort under a large tarp. When the owner pulled the tarp back, David realized he was looking at a partially built replica Ford GT40 built by a UK kit-car company.

The guy had brought it into New Zealand under a 12-month Carnet (a Carnet de Passages en Douane allows a person to bring a car into a country for a specific timeframe with a hefty bond paid to ensure that the owner ships it back). Nine months was up, meaning it had to go back to his home in Aussie soon, and it needed to be completed in a hurry. Having plenty of work already, and not wanting to be involved with someone else’s replica, David politely but firmly declined the pleas for him to finish the car.

A couple of weeks rolled by, and the guy had made several calls to David trying to talk him into working on the car. He phoned once again, and this time told David he was shipping it down, and it would be there in a couple of days.

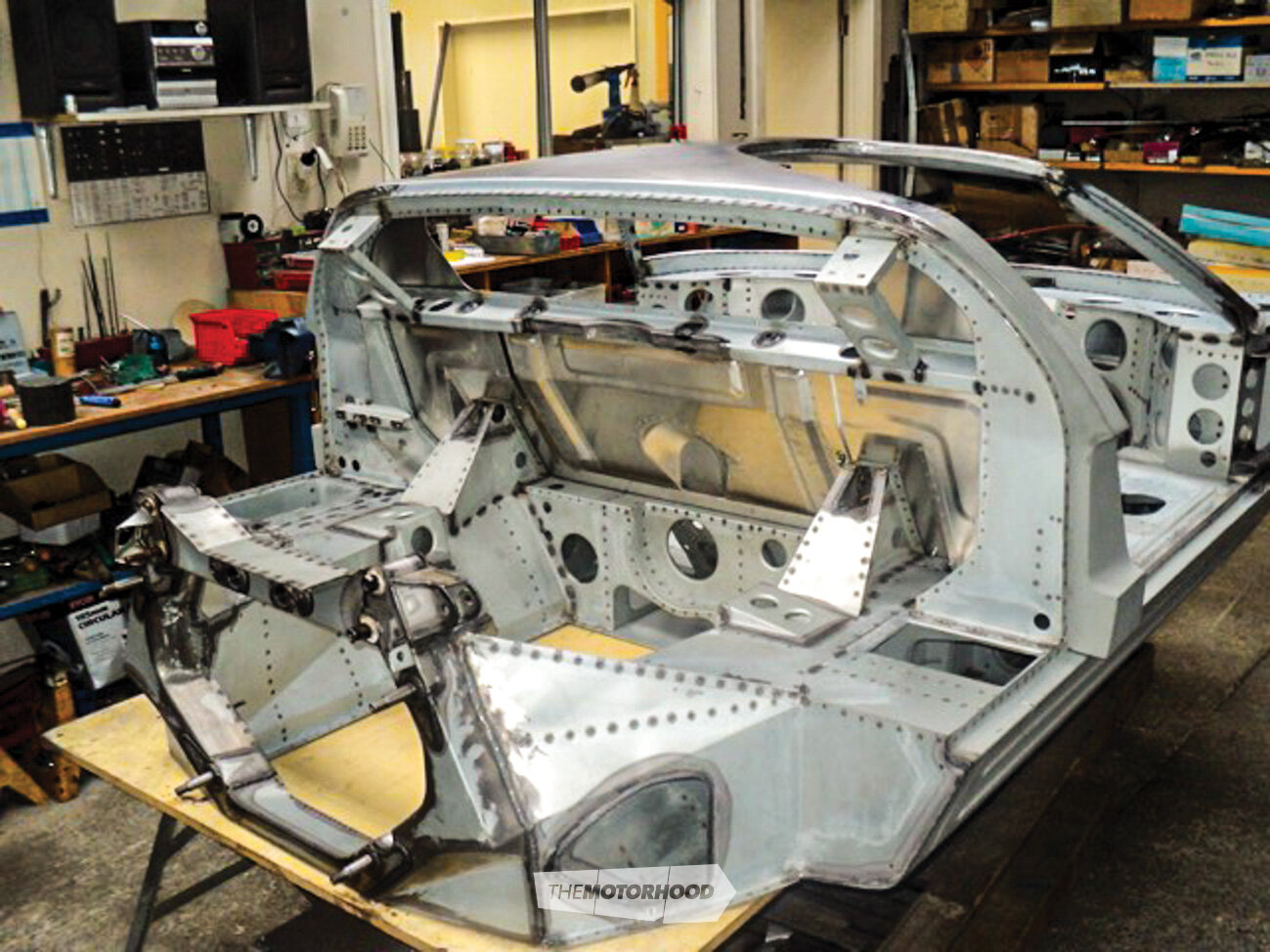

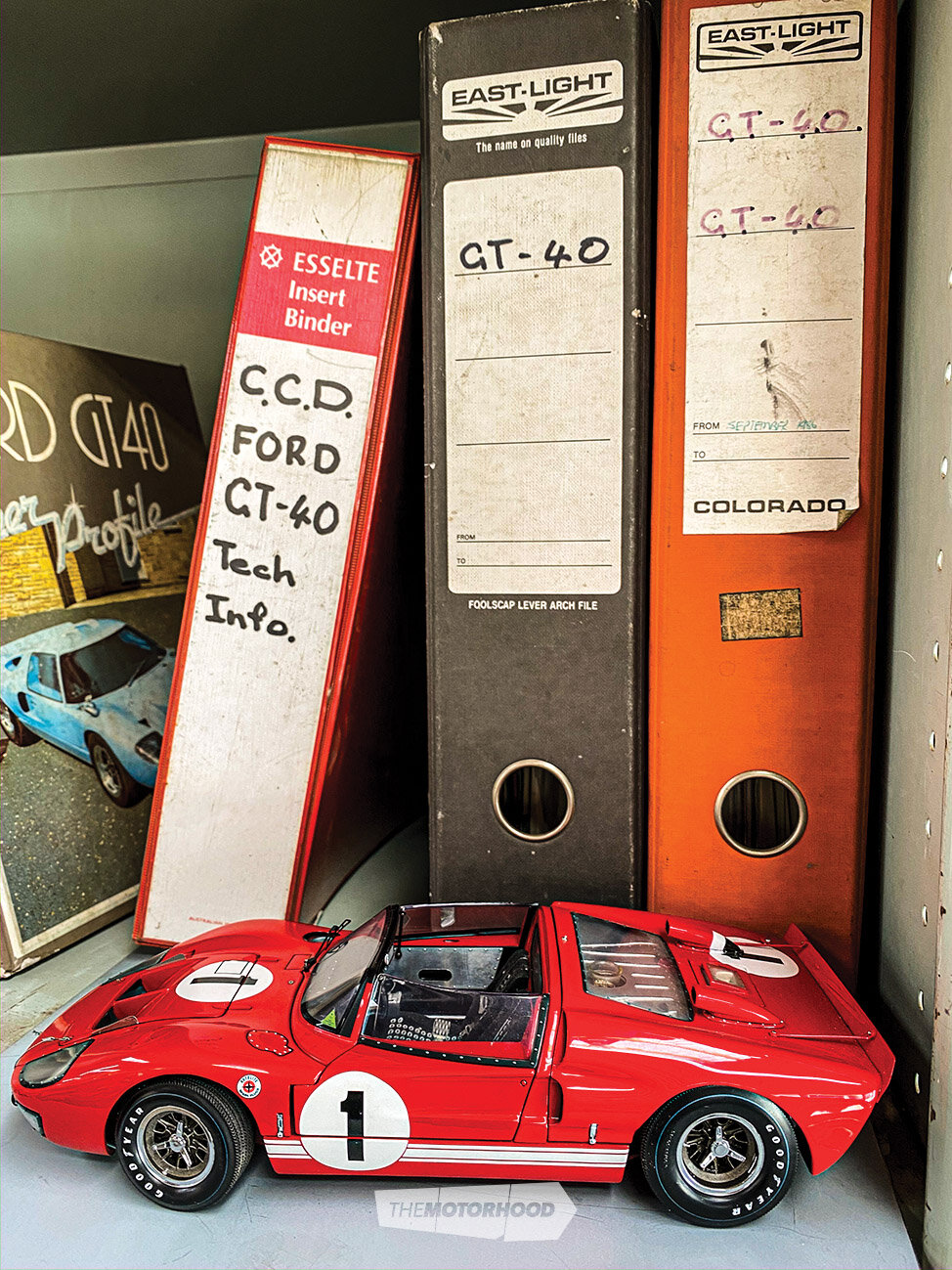

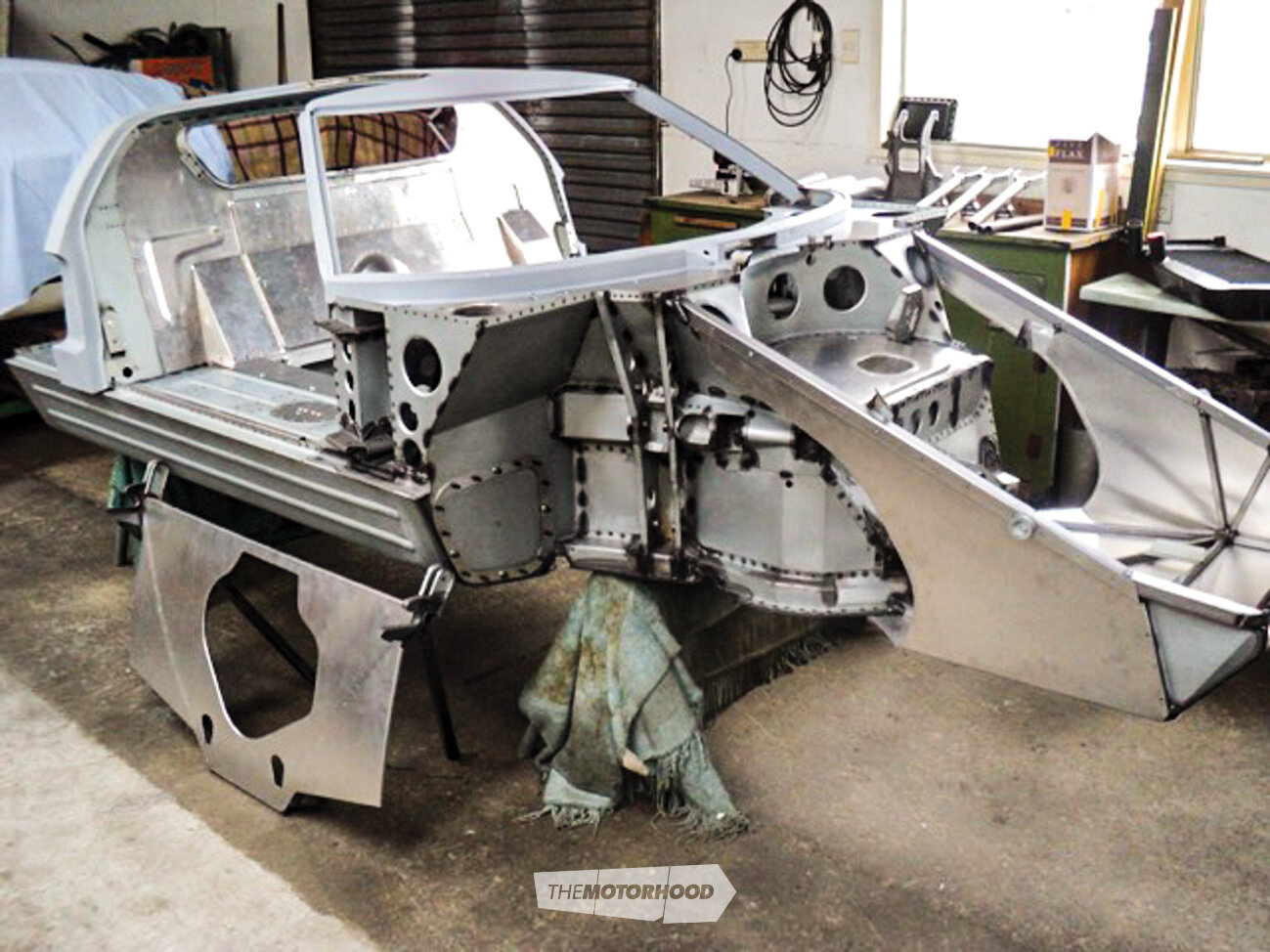

When the car arrived, and David inspected the chassis, he quickly realized it was a complete mess, wasn’t straight, and was constructed out of super-heavy rectangular hollow section (RHS). David convinced the owner it wasn’t worth working with, and, luckily, the owner agreed to doing it properly with a full 100-per-cent construction, faithful to the original monocoque chassis of a real GT40. Dave had no inclination to build anything else than Jaguar C- or D-Types, but he got interested in the build when he realized how well the GT40s were designed and built. Being a fastidious researcher, this sent him into a tailspin of burning the candle at both ends, researching every last millimetre of the GT40’s construction. This often extended late into the evenings, looking at drawings and photos from library-sourced books with a magnifying glass to ensure that he understood every panel, every fold, every opening, every spot-weld, and the placement of every rivet. A major help to this was building a connection and friendship with Brian Wingfield from the UK, who had worked on all the original GT40s. Brian helped hugely by giving David lots of information, drawings, and all the original dimensions to help solve the life-sized 3D jigsaw puzzle. David’s precision aircraft engineering background helped immensely with the ground-up datum-line construction of fabricating bulkheads and panels, placing panels using clecos, then riveting and spot-welding everything together, exactly as the original cars were made. Of course, with a build like this, everything has to be absolutely correct in measurements and angles for each piece to fit together precisely.

The original Ford GT40 was designed and built in England, based on the British Lola Mk6 and was produced in three models: the MkI, MkII, and MkIII variants. Only the MkIV model was fully designed and built in the US. Contrary to what a lot of Americans think — or wish — this was truly a British-manufactured race car, albeit with an American V8, made to specifically race and win at Le Mans, which it eventually did. In 1966, the GT40 ended Ferrari’s 1960–’65 24 Hours of Le Mans race–winning streak by taking first, second, and third places. The GT40s then continued to win the next three Le Mans races in ’67, ’68, and ’69.

The GT40 range was powered by a series of Ford V8 engines, modified for racing. Early cars were simply named ‘Ford GT’ (for ‘grand touring’), which was the name of Ford’s project to prepare the cars for the international endurance racing circuit. The ‘40’ represented its height of 40 inches, measured at the windshield, the maximum allowed for Le Mans racing. The purchase price in 1964 for the completed car for competition use was £5200.

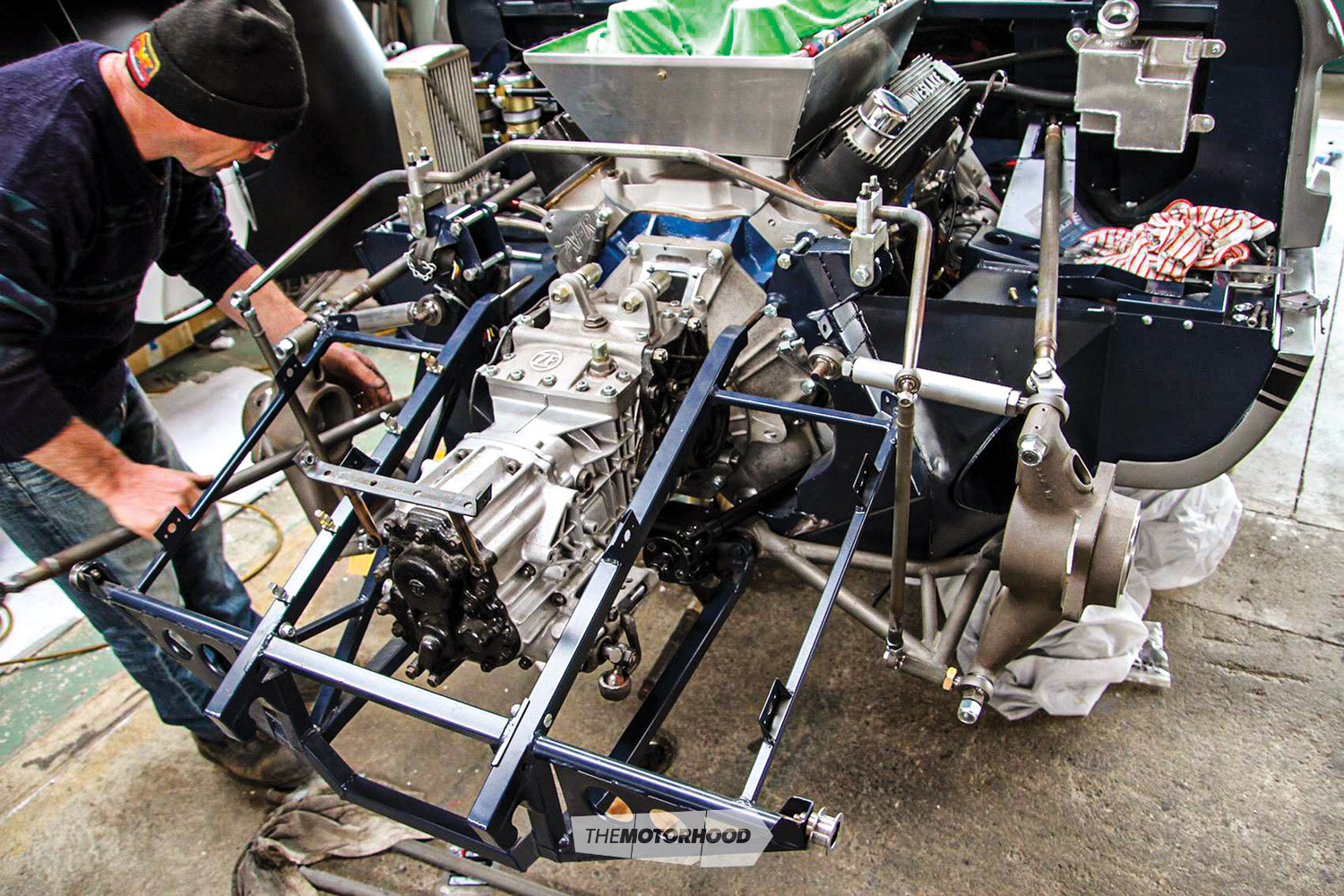

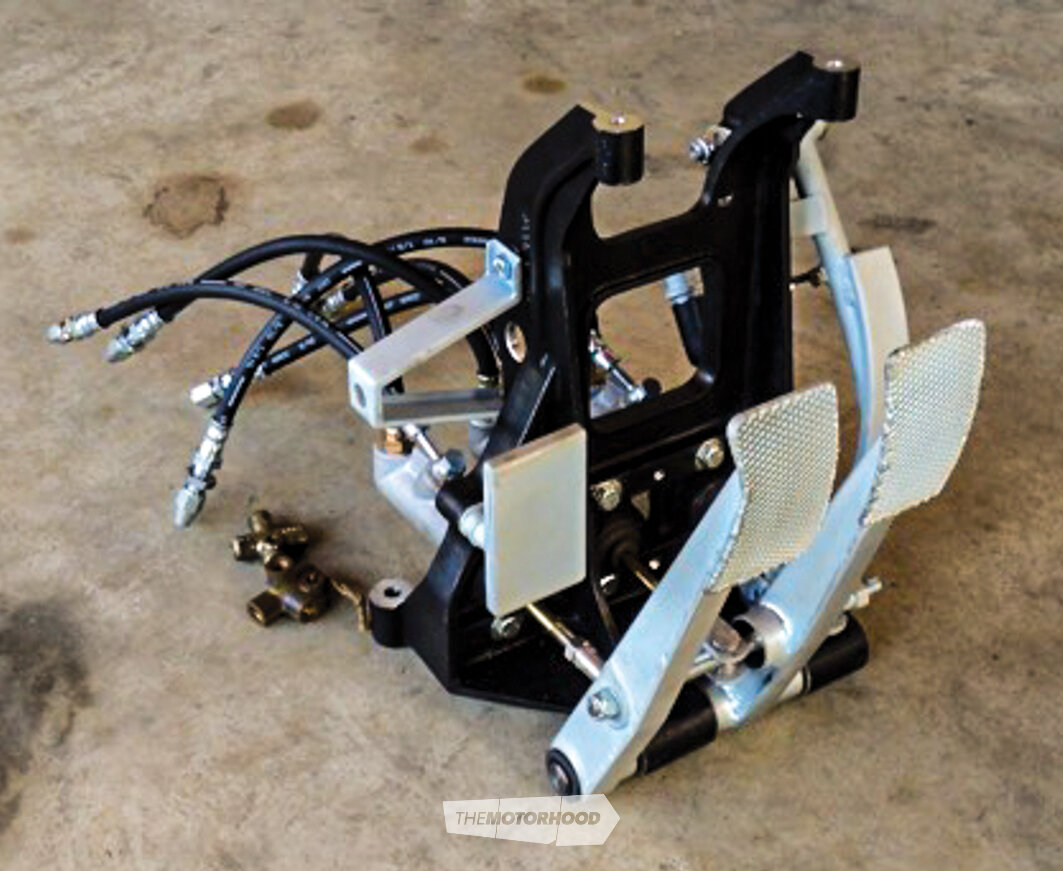

GT40s have a full monocoque chassis construction (the word ‘monocoque’ is a French term meaning ‘single shell’) rather than a tube space frame favoured by many manufacturers for limited-build race cars, so the chassis is mostly constructed out of very light, 22-gauge zinc sheet. By itself, a flat sheet has little strength. However, when it is folded into intricate shapes, it gains massive compression and shear strength, producing a rigid chassis as good as a modern mass-produced car. Not to be taken lightly, over 700 panel components go into building a GT40 chassis, with very few parts being identical. The cockpit is designed to be exclusively right-hand drive, with a 2¾-inch bias of the driver’s side off the centre line. David has spent countless hours building tooling, dies, jigs, and formers to produce one of the most accurate replica chassis in the world. On top of building the patterns for every chassis part, David has constructed over 70 patterns for casting other parts such as suspension uprights, gear-lever brackets and bearing holders, body hinges, pulleys on the engine, and the pedal box. He mostly uses Wickham Foundry in Christchurch for the alloy cast parts and Casting Shop Ltd, also in Christchurch, for the cast parts. David runs a small, highly skilled team of machinists and sheet-metal fabricators, and, with years of engine reconditioning experience and many Ford V8 rebuilds, David completes the engine rebuilds himself and has a local specialist in Invercargill work on the ZF transmissions if necessary.

The car in the photos is owned by Brian Stewart from Dunedin and is the only GT40 that David has built for a New Zealander. It is fitting that Brian chose its registration number and car roundel numbers in recognition of GT40P 1046, the car that was driven to victory in the 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans race by New Zealanders Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon.

True to the original, the body has fibreglass front and rear body sections, and fibreglass doors. And, after much deliberation, Brian chose a 1969 351W engine — complete with 0.030-inch overbore, giving a total of 5833cc displacement — with AFR 185cc aluminium heads, yielding over 400bhp. This is mated to a ZF transaxle, with Girling four-pot alloy calipers on the front, and Girling 16/4s on the rear — both as on the ’68 and ’69 Le Mans–winning car — to handle stopping duties.

Early prototype GT40s were fitted with Ford’s 255ci, four-cam, ‘Indy’ engine, and production MkI racers were fitted with small block 289s, or, in later years, 302 engines. However, some cars, including the three GT40-based Mirages, ran 351W-derived engines for a few races. The MkIIs and MkIVs ran big block 427ci FEs, and, of the 107 built — 134 if you include MkIIs, IIIs, IVs, and Mirages — it is thought that only seven cars no longer exist. Exact numbers are not clear, because some cars were rebuilt using different chassis numbers, or changed designation, or their fate is unknown. There is also some doubt about the pedigree of some supposedly original cars, with more than one car showing up with the same chassis number.

Ford made use of its extensive parts bin for the GT40, with a number of items being sourced from more mundane company products, and additional items were either sourced from other makes current at the time and modified to suit, or custom-built. Many of the items required to build this car were collected by Brian during an exhaustive 18-year search within New Zealand and around the globe. The remainder were sourced or custom-fabricated by David.

For durability and longevity, there are a few subtle upgrades built into Brian’s car. For example, the original MkIs were fitted with Rotoflex drive couplings, but his car has CV joints, as found on MkIIs. The original uprights, pedal box, steering rack, filler caps, and wheels were magnesium, but on his car they are aluminium for longevity. The original fuel tanks were rubber-bladder type, which were prone to leaks and had a limited lifespan, so CCD built beautifully fabricated aluminium tanks. Also installed is a plumbed-in fire-suppression system, which the originals did not have, although many have since had such systems retrofitted. The original monocoque chassis were not made from zinc-coated steel, so were prone to rust. The original cars had a cable-driven speedo and mechanical gauges, but Brian has fitted his car with ultra-reliable Smiths electronic gauges.

The early original cars also had heavy, cast-iron heads, so, to save some weight, Brian has fitted his with aluminium heads and front cover, saving about 40kg. However, some later original race cars were fitted with the lighter aluminium Gurney Weslake heads. Brian’s brake discs are ventilated, to give better cooling than the solid discs that were used on early (pre-1966) originals, and the tyres chosen are Avon CR6ZZs. The original cars used Goodyear Blue Streaks, among others. However, many originals now involved in classic racing are shod with Avons where allowed.

The original mechanical water pump has been replaced with an electric pump to facilitate cooling in slow or stop-start traffic, while the original racing intake manifold has two coolant outlets, no thermostat housing, and Webers all facing left.

This car has a single-outlet manifold and Webers facing away from each other.

Acceleration from zero to 62mph is a shade under four seconds and top speed, with the current gearing, is approximately 165mph at a modest 6000rpm. With Le Mans gearing and in race tune rather than street, it would likely top 200mph, as a number of the GT40 MkIIs were clocked at speeds well in excess of 210mph on the Mulsanne Straight during the 1966 race. They had 80hp more than this car, but were 100kg heavier.

When asked what it’s like to drive, his reply is, “Just like the originals: hot, noisy, little room for luggage, and leaks like a sieve in the rain. But it handles brilliantly, and driving it is huge fun. It is surprisingly comfortable, and it is possible to hold a conversation with your passenger at 100kph [62mph] … just.”

A couple of interesting facts about the GT40’s aerodynamics: when the car is coming towards you at pace, the induction noise of air being fed out of the engine bay and sucked back into the air intakes creates a ‘singing’ noise, and when a GT40 goes through dust on the road, the dust swirls at the rear from each side in towards the centre due to the two vortices caused by the shape of the smooth body with the sharply cut-off rear end. The 180-degree headers also give a sound very unlike the usual V8 throb.

With five completed GT40 cars and 16 rolling chassis shipped from David’s Invercargill workshop to Norway, Sweden, the UK, France, the US, Australia, and New Zealand, it’s a real tribute to him that his cars and chassis are raced and displayed at famous tracks all over the world, including Goodwood and Silverstone. His business is certainly unique and is very unconventional compared with a normal New Zealand business. He does zero marketing, as it is all word of mouth; has no website; isn’t on any social media; and his enquiries are a phone call from somewhere in the world every three months or so. The people who call normally know exactly what they are wanting and are serious about ordering a car.

So, if you want to buy yourself an incredible, handmade car that is a slice of ’60s V8 racing history, be warned, you better know your GT40s, and David jokes that you only get two choices when he builds you a car — the colour and the brand of tyres you want to run!

This article originally appeared in NZV8 issue No. 185